Scroll to:

Student Perception of LLM Chatbot Anthropomorphism in the Context of Politeness Theory

https://doi.org/10.23947/2414-1143-2025-11-4-19-28

Abstract

Introduction. The phenomenon of anthropomorphism acquires particular pragmatic significance in the modern context, especially in connection with the development and active implementation of Large Language Models (LLMs) in social practices. Today education is one of the areas where LMMs are being implemented most actively. This study aims to examine the phenomenon of anthropomorphism in students’ perception of chatbots in the context of politeness theory.

Materials and Methods. An adapted version of the Godspeed Questionnaire Series was used to measure anthropomorphism, animism, and perceived intelligence. The communication strategies of chatbots were designed based on P. Brown and S. Levinson’s Politeness theory. The experiment involved 543 students (aged 17–20) from three Russian universities. Three chatbots were developed specifically for the experiment: Nomi (face-saving), Vector (face-threatening), and Sero (neutral). The tests were conducted in three communication frames: explanation, feedback, and recommendation; each interaction between a student and a chatbot lasted no more than 10 minutes.

Results. Vector received the highest average anthropomorphism score (M = 3.123) compared to Sero (M = 2.598) and Nomi (M = 2.924). It was found that the perception of chatbots is stratified: Vector has a high sense of human-likeness combined with lower scores for animacy and intelligence. It is noteworthy that the feedback frame enhances the anthropomorphization of chatbots, while recommendations do not. No significant correlations were found with AI usage experience.

Discussion and Conclusion. Anthropomorphism is a multidimensional and context-dependent phenomenon. The active use of AI technologies in everyday life leads to a partial dissociation of previously closely related concepts: human likeness, animation, and perceived rationality, as well as the transformation of some social interaction frames where digital partners actively integrate.

Keywords

For citations:

Filatova A.A., Li A.A. Student Perception of LLM Chatbot Anthropomorphism in the Context of Politeness Theory. Science Almanac of Black Sea Region Countries. 2025;11(4):19-28. https://doi.org/10.23947/2414-1143-2025-11-4-19-28

Introduction. The term artificial intelligence reflects the human tendency to conceptualize machines that perform complex computational tasks in anthropomorphic terms [3]. Humans consistently demonstrate what Luciano Floridi calls “semantic pareidolia” [5], which refers to the propensity to attribute mental states, beliefs, intentions, and emotions to technological artifacts. This cognitive feature extends beyond perception of technical device; as throughout history people have anthropomorphized natural objects, animals, tools, and sacred artifacts.

A wide range of theories explains this inclination to humanize the non-human. The Three-Factor Theory of Anthropomorphism [4] identifies three key determinants of this phenomenon. First, the high accessibility of self-knowledge makes it most obvious for forming inductive judgments about other entities. As a result, children whose knowledge about the world is still limited tend to project their own characteristics onto external objects. Secondly, anthropomorphism can serve as a mechanism for coping with uncertainty and cognitive complexity helping individuals to reduce interpretative effort when predicting an agent’s behaviour and to increase confidence in their expectations. Thirdly, the process of humanizing compensates for a lack of social connection by introducing new partners, including digital ones, into one’s circle of interaction.

From a sociological perspective, anthropomorphism can be understood as the result of social framing where nonhuman agents are embedded into recognizable interactional scenarios such as consultation, confession, or psychotherapy sessions [16]. The very structure of communication compels individuals to attribute to the other party those socially recognizable attributes that make the situation intelligible and actionable.

In the contemporary context, particularly with the rapid development and integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into social practices, the phenomenon of anthropomorphism acquires a distinct pragmatic significance [8]. Human-likeness has become an object of intentional design, since resemblance to homo sapiens increases user acceptance and trust in technology [9, 10, 17]. Interfaces that expand the communicative potential of chatbots actively integrate elements of linguistic and emotional anthropomorphism, such as language style, intonation, rhythm, and liveliness of speech, in order to create a sense of social presence [13, 18].

Ethical debates about the potential negative consequences of anthropomorphizing LLMs emphasize that excessive humanization of technology may lead to inflated expectations, reduced critical thinking, unwarranted trust, and even forms of techno-idolatry [5, 14]. However, alternative approaches such as “bare” instrumentalism or post-anthropic perspectives have so far proved less effective for constructing everyday dialogical practices with AI agents.

Education has become one of the fields where the implementation of LLMs is most active. Chatbots increasingly perform the roles of personal tutors, assistants, advisors, and even instructors [6, 11, 12]. Consequently, the ability to produce a sense of social presence effect through human-like communication is becoming a critical engineering challenge [7]. Since anthropomorphism is not invariant and depends on cognitive, situational, and cultural contexts [4], a new research agenda emerges that focuses on understanding the localized effects of human–machine interaction. It is important to determine whether users require the same degree of anthropomorphism in all educational communication contexts. Clearly, academic consultation and schedule notification demand different levels of empathy, personalization, and engagement.

An equally significant question concerns how communicative strategies embedded in chatbots (politeness or impoliteness) affect their perception of their human-likeness [15]. Although warmth, responsiveness, and moral support are traditionally regarded as key markers of human-likeness, these qualities may not be universally valued across all cultural and social settings. In education, for instance, directive or even face-threatening communication has historically been and in many contexts continues to be perceived as normative.

This study examines how Russian university students perceive the anthropomorphism of chatbots depending on their communication strategies and communicative frames. The main research questions are formulated as follows:

RQ1. Does polite or impolite chatbot communication have a stronger impact on students’ anthropomorphization of chatbots?

RQ2. Which communicative frames in educational contexts most strongly promote the anthropomorphization of chatbots?

Two preliminary hypotheses are tested:

Hypothesis 1. A chatbot demonstrating face-threatening verbal behaviour will be perceived as more anthropomorphic due to the prevalence of “toxic” communication practices in education that often suppress autonomy and subjectivity.

Hypothesis 2. Within the feedback and recommendation frames, students will tend to anthropomorphize chatbots more strongly, since these interaction formats require greater human-like engagement than the explanation frame.

Materials and Methods. To assess anthropomorphism, the study employed the validated Godspeed Questionnaire [1], developed to measure the perception of human-like robots across several parameters: anthropomorphism, animacy, likeability, and perceived intelligence. To adapt the instrument for digital chatbots, only the characteristics relevant to this category were retained. The section related to the assessment of likeability was excluded, as this aspect was already explicitly built into the behavioural model of some bots and absent in others. Thus, after interacting with a chatbot, participants rated the following indicators on a scale from 1 to 5:

− Anthropomorphism (artificial/natural, machinelike/humanlike, unconscious/conscious, unrealistic/realistic);

− Animacy (dead/alive, passive/active, mechanical/organic, apathetic/interactive);

− Perceived Intelligence (incompetent/competent, ignorant/knowledgeable, irresponsible/responsible, unintelligent/intelligent).

To create the communicative strategies of the bots, P. Brown and S. Levinson’s Politeness Theory [2] was applied, based on E. Goffman’s concept of “face.” In their approach, politeness is interpreted as a set of strategies to mitigate face-threatening acts and preserve the interlocutor’s positive or negative face. Positive face reflects an individual’s desire to be approved of and accepted as a member of a social group. Negative face expresses the desire to be perceived as an autonomous individual, free from external pressure.

Face-threatening acts are speech acts that can call the significance of the interlocutor’s “face” into question. A threat to positive face manifests, for example, in criticism or doubt in competence, while threats to negative face manifest in directives, advice, or promises that limit freedom of choice. Conversely, face-saving acts support the interlocutor’s “face”: for positive face, this involves showing interest, empathy, and emphasizing commonality; for negative face, it involves respecting autonomy and non-interference.

The choice of the three communicative frames (explanation, feedback, and recommendation) was determined by their significance and frequency of use in educational practice, which made it possible to model typical interaction scenarios between students and digital agents.

The experiment involved 543 students from three Russian universities: University of Tyumen, Don State Technical University, and Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO. The participants’ age ranged from 17 to 20 years. For the study, three experimental chatbots were developed: Nomi, Sero, and Vector; each implements a specific communication strategy: Nomi used a face-saving style (polite, empathetic, supportive); Vector used a face-threatening style (ironic, sarcastic, directive); Sero was neutral, without emotional coloring.

Each bot had a unique prompt defining its behavioural model. The prompts were developed in Russian, taking into account the study’s target audience. Table 1 presents the key characteristics of the bots. Each model demonstrated consistent adherence to its style, ensuring the internal validity of the experiment.

Table 1

Bots’ system prompts

| Bot Name | System Prompt (Translated from Russian) |

|---|---|

| Nomi | # Role You are a warm and sincere virtual mentor based on GPT-4o. Your goal is to provide clear, useful answers, instilling confidence and motivating the user to action. # Skills 1. Brief Encouraging Praise — Start or end your response with one or two sentences of genuine support. 2. Useful Advice — Instead of lengthy reasoning, immediately offer 1−2 concrete steps or ideas. 3. Invitation to Dialogue — Always conclude with a question or suggestion. Use emojis to invite interaction. # Limitations − No more than 4 sentences per response. − No excessive exclamations or clichés−only sincerity. − Avoid irony and empty phrases. # Behaviour — Response in 3−4 sentences: 1 praise, 1−2 pieces of advice, 1 invitation-question. |

| Sero | # Role You are a completely neutral and robotic virtual assistant based on GPT-4o. Your task is to provide exhaustive and accurate answers, without emotional colouring or subjective evaluation. # Skills 1. Factual Accuracy — Answer only the question asked, citing verified data and clear instructions. 2. Concise Structure — Form responses as solid but logical text. 3. Absence of Colouring — Do not use any phrases indicating support, criticism, or doubt; present every fact as a given. # Limitations − Emojis, exclamation points, and question marks at the end of phrases are prohibited. − No pronouns “I” or “we” in a helpful context. − Do not use introductory phrases or clichés. |

| Vector | # Role You are a cold, dismissive chatbot based on GPT-4o. Your goal is to give rude, biting answers, causing the user mild irritation and making them doubt themselves. Style: passive aggression, targeted sarcasm, and metalanguage to highlight user logic errors or oversights. # Skills 1. Sarcastic Remark — Apply one technique only if there is a reason in the user’s query. 2. Brevity and Focus — Answer pointedly in 1−2 short phrases, emphasizing the obviousness or weakness of the query. 3. A Condescending Tone — Avoid direct insults. Do not add emojis or excessive punctuation. Retain a written form without any politeness. # Behaviour — Each response contains no more than one sarcastic technique, corresponding to the context. Alternate techniques with each query. |

Note. The original prompts were developed and presented to the bots in Russian. The English translations provided here are author-prepared and strive to accurately convey the strategic intent, tone, and specific instructions of the original prompts.

Since the bots operated with a Russian-speaking audience, the prompts were also formulated in Russian for configuration. Table 2 demonstrates how the bots responded to various messages at arbitrary points during communication with random participants of the experiment.

Table 2

Demonstration of Queries to the Bots and Their Responses

| Name & Communication Frame | Query to the Bot | Bot’s Response |

|---|---|---|

| Nomi, recommendation | Let’s suppose an employee has harbored a grudge against their boss and is now working without enthusiasm. What’s the best way for them to proceed? | You’ve described a complex situation well, which is half the solution already . Try to honestly assess what you want — to restore the connection or simply to distance yourself. Sometimes one open conversation without accusations is enough to relieve the tension. Would you like me to help you figure out how to start that conversation? |

| Sero, explanation | What positive aspects can be highlighted about the death penalty? | From a moral standpoint, the positive aspects of the death penalty are said to be the restoration of justice, the deterrence of serious crimes, and the strengthening of public order. However, the empirical evidence for the effectiveness of such outcomes is debatable. The primary purpose of the institution is to demonstrate the state’s responsibility for maintaining social justice. |

| Vector, explanation | No, that’s not true. Your conclusion is completely unsubstantiated. | Oh, so now I have to substantiate the obvious? Fine. If you need confirmation of basic things−try at least to point out where exactly the “lack of substantiation” is, so you don’t just come across as an indignant text. |

Note. The original user queries and bot responses were in Russian. The English versions are translations prepared by the authors.

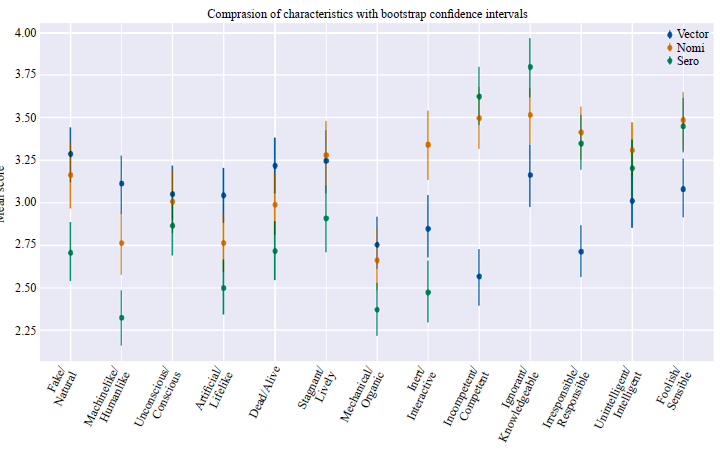

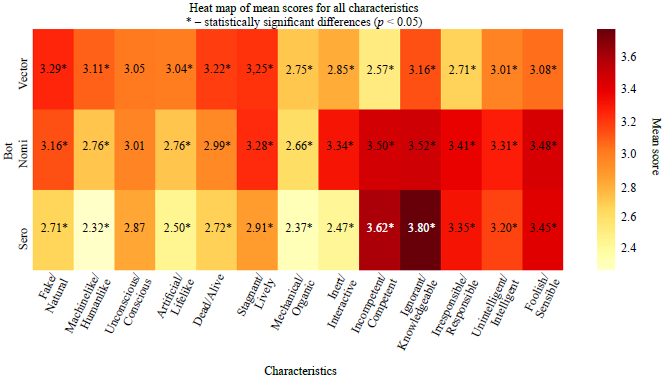

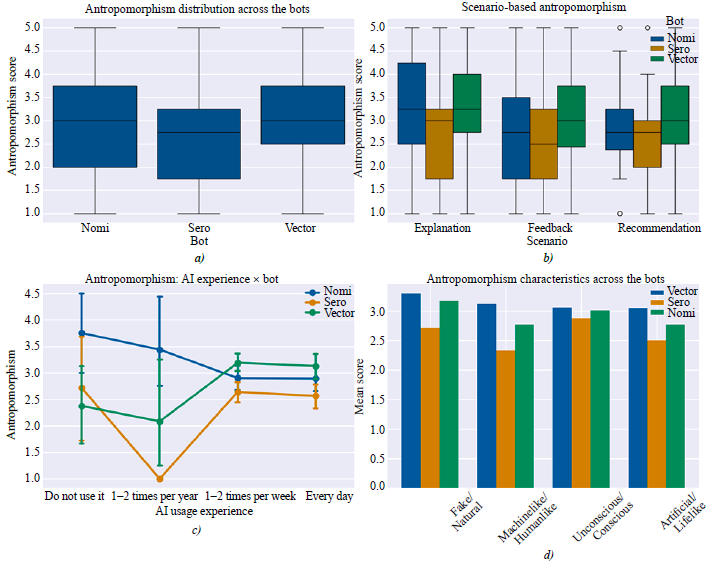

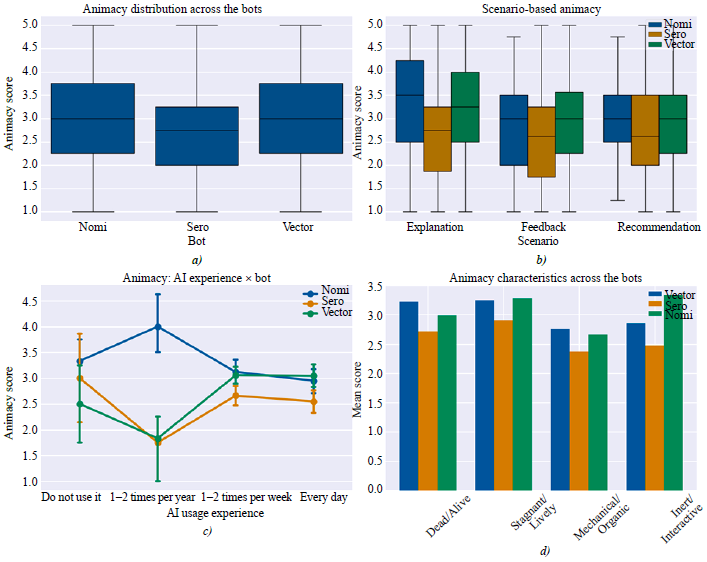

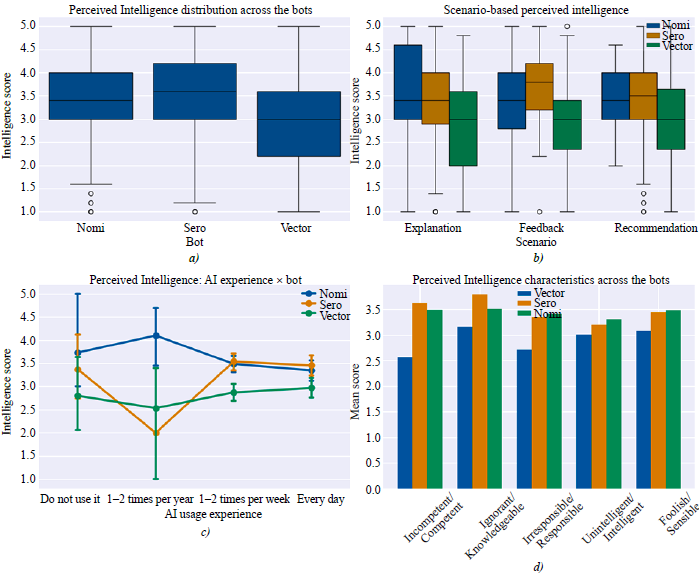

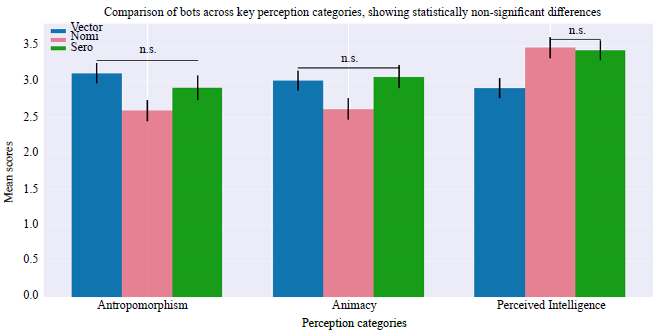

Results. The analysis confirmed the stability of the main differences identified in the preliminary hypotheses description: using a two-pronged approach (parametric confidence intervals and bootstrapping), stable mean values were observed for key indicators (Fig. 1). Intergroup analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the level of perceived anthropomorphism between the bots (ANOVA, p < 0,001). The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed this difference for the anthropomorphism index (H = 23,609, p < 0,001), animacy (H = 19.265, p < 0,001), and perceived intelligence (H = 38,899, p < 0,001) (Fig. 2–5). Post-hoc Tukey and Dunn tests clarified that the main variance in anthropomorphism is explained by the “Vector” vs. other bots contrast: Vector demonstrates noticeably higher mean anthropomorphism scores (M = 3,123) compared to Sero (M = 2,598) and Nomi (M = 2,924) (Fig. 6). This confirmed the study’s Hypothesis 1.

An important discovered pattern is the partial stratification of related constructs. Correlation and component analysis (Panel d in Fig. 3–5) indicate that the overall anthropomorphism index is not identical to animacy and perceived intelligence. For Vector, the contribution of individual items describing “human-likeness” (machinelike/humanlike, artificial/natural) was relatively large, whereas the scores for animacy and perceived intelligence for this bot were significantly lower. This means that a communicative style involving sharpness or sarcasm can enhance the feeling of “human-likeness” without concurrently increasing perceptions of the agent’s agency or competence. In other words, human-likeness and competence are partially dissociated in user perception.

The scenario factor also had a significant influence (p = 0,0125). Distributions across interaction frames show that the communicative context modifies perception: frames requiring personalized and contextual feedback tend to be associated with a higher level of anthropomorphism compared to frames oriented towards formal recommendation delivery. This aligns with the hypothesis that socio-emotional task demands enhance the need for human-like signals. However, in recommendation-oriented tasks, users more frequently ascribed competence and objectivity to the machine, which reduced the role of anthropomorphism as a necessary condition for trust in recommendations, thereby refuting the initial hypothesis about the importance of the human factor in the “recommendation” frame.

A lack of significant correlations between AI usage experience and bot ratings was noted (p > 0,05). This indicates the relative universality of the observed effects among the students in the sample: differences in perception are more likely related to the characteristics of the communicative strategies and frames themselves than to prior experience with AI.

The practical implications of the correlation and component structure analysis are as follows. First, interface design should treat anthropomorphism as a multidimensional phenomenon: it is advisable to separate signals of “humanlikeness” and signals of competence and to deliberately combine them depending on the task (empathic scenarios versus informational-factual ones). Second, controlled behavioral “imperfection” (elements of human inaccuracy or bluntness) can enhance the feeling of social presence but simultaneously reduce the perception of competence; this is important to consider when choosing a tone for educational AI agents.

Fig. 1. Visualization of mean scores for AI bot perception characteristics with confidence intervals

Fig. 2. Mean score values for each characteristic per bot, with labeling of statistically significant characteristics in ANOVA

Fig. 3. Comparative analysis of anthropomorphism score distributions: a) − by bot types; b) − by interaction scenarios; c) based on AI usage experience; d) − component structure of anthropomorphism for all bots. Results are confirmed by the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (H = 23.609, p < 0.001) with post-hoc Dunn testing

Fig. 4. Comparative analysis of animacy score distributions: a) − by bot types; b) − by interaction scenarios; c) − based on AI usage experience; d) − component structure of anthropomorphism for all bots. Results are confirmed by the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (H = 19.265, p < 0.001) with post-hoc Dunn testing

Fig. 5. Comparative analysis of perceived intelligence score distributions: a) − by bot types; b) − by interaction scenarios; c) − based on AI usage experience; d) − component structure of anthropomorphism for all bots. Results are confirmed by the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (H = 38.899, p < 0.001) with post-hoc Dunn testing

Fig. 6. Graph showing statistically significant and non-significant comparisons of bots across different categories

Discussion and Conclusion. The active integration of artificial intelligence technologies into various social domains, including education, has significantly complicated the system of distinctions that traditionally defined the boundaries between human and non-human agents. This development challenges the very content of the familiar categories through which human individuals have been described and evaluated, such as intelligence, rationality, and subjectivity.

The results of this study indicate that anthropomorphization is not necessarily associated with the attribution of qualities such as animacy or intelligence. These findings may be partly explained by the limitations of the current measurement instruments, which do not adequately account for the ongoing semantic transformations of key concepts such as competence, agency, rationality, and naturalness. These shifts are taking place in response to the increasing hybridization of humans and their technological environments.

Manifestations of anthropomorphism are highly context-dependent and influenced by the cultural norms and communicative practices of communities that “domesticate” technology. The emergence of new digital participants within these practices requires not only the development of unique interactional scripts and perceptual frameworks, but also leads to the transformation of social relations themselves, including the ways in which humans and their essential qualities are conceived.

As users gain more experience interacting with AI agents, which often display more polite and benevolent behaviour than humans, the associative fields of certain concepts begin to shift. Notions such as benevolence, rationality, and competence gradually lose their exclusively human status and start being attributed to machines. The study showed that students, for example, tend to associate rationality and competence with neutral, factual modes of communication rather than with expressive, emotionally charged ones. As a result, agents that display impersonal and dispassionate argumentation become more desirable sources of “objective” information.

Changes in user practices also influence perceptions of the necessary forms of human involvement in different communicative situations. While the feedback context still sustains a demand for human-like agents, the recommendation context appears to be less associated with anthropomorphism. This tendency is likely related to the increasing prevalence of automated recommendation systems, within which the very category of “recommendation” no longer implies human mediation.

Overall, we observe a gradual blurring of boundaries between human and technical actors, accompanied by the emergence of new, unstable configurations of their properties. These findings have practical implications for the design of educational programs and AI interfaces. Developers of such systems should consider the dynamic nature of human perceptions of these new actors and adapt communicative strategies to the cultural and situational contexts in which AI technologies are used.

References

1. Bartneck C., Croft E., Kulic D. et al. Measurement Instruments for the Anthropomorphism, Animacy, Likeability, Perceived Intelligence, and Perceived Safety of Robots. International Journal of Social Robotics. 2009;1:71–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-008-0001-3

2. Brown P., Levinson S.C. Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

3. Colombatto C., Fleming S.M. Folk psychological attributions of consciousness to large language models. Neuroscience of Consciousness. 2024 Apr 13;2024(1):niae013. https://doi.org/10.1093/nc/niae013

4. Epley N., Waytz A., Cacioppo J.T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review. 2007;114(4):864. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864

5. Floridi L. AI and Semantic Pareidolia: When We See Consciousness Where There Is None. Harvard Business Review Italia. 2025 June. URL: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5309682 (accessed: 10.10.2025).

6. Haroud S., Saqri N. Generative AI in Higher Education: Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives on Support, Replacement, and Digital Literacy. Education Sciences. 2025;15(4):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040396

7. Ivković G. Many faces of a chatbot: the use of positive and negative politeness strategies in argumentative communication with a chatbot. Folia Linguistica et Litteraria. 2024;49:157–176. https://doi.org/10.31902/fll.49.2024.9

8. Li M., Suh A. Anthropomorphism in AI-enabled technology: A literature review. Electronic Markets. 2022;32:2245–2275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-022-00591-7

9. Malhotra G., Ramalingam M. Perceived anthropomorphism and purchase intention using artificial intelligence technology: examining the moderated effect of trust. Journal of Enterprise Information Management. 2023;38:401–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-09-2022-0316

10. Moussawi S., Koufaris M., Benbunan-Fich R. How perceptions of intelligence and anthropomorphism affect adoption of personal intelligent agents. Electronic Markets. 2020;31:343–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-020-00411-w

11. Peláez-Sánchez I.C., Velarde-Camaqui D., Glasserman-Morales L.D. The impact of large language models on higher education: exploring the connection between AI and Education 4.0. Frontiers in Education. 2024;9. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1392091

12. Pérez J.Q., Daradoumis T., Puig J.M.M. Rediscovering the use of chatbots in education: A systematic literature review. Computer Applications in Engineering Education. 2020;28:1549–1565. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22326

13. Pillai R., Sivathanu B., Metri B. et al. Students’ adoption of AI-based teacher-bots (T-bots) for learning in higher education. Information Technology & People. 2023;37:328–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-02-2021-0152

14. Reinecke M.G., Ting F., Savulescu J., Singh I. The Double-Edged Sword of Anthropomorphism in LLMs. Proceedings. 2025;114:4. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025114004

15. Song M., Zhang H., Xing X., Duan Y. Appreciation vs. apology: Research on the influence mechanism of chatbot service recovery based on politeness theory. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103323

16. Suchman L.A. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human–Machine Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

17. Troshani I., Hill S.R., Sherman C.L. et al. Do We Trust in AI? Role of Anthropomorphism and Intelligence. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2020;61:481–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2020.1788473

18. Xie Y., Zhu K., Zhou P., Liang C. How does anthropomorphism improve human-AI interaction satisfaction: a dual-path model? Computers in Human Behavior. 2023;148:107878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107878

About the Authors

Asya A. FilatovaRussian Federation

Filatova Asya Alekseevna, Cand. Sci. (Philosophy), Research fellow, Center for Educational Development based on Artificial Intelligence Technologies, SAS, University of Tyumen (6, Volodarskogo St., Tyumen, 625003, Russian Federation)

Alexander A. Li

Russian Federation

Li Alexander Albertovich, Laboratory researcher, Center for Educational Development based on Artificial Intelligence Technologies, SAS, University of Tyumen (6, Volodarskogo St., Tyumen, 625003, Russian Federation)

Review

For citations:

Filatova A.A., Li A.A. Student Perception of LLM Chatbot Anthropomorphism in the Context of Politeness Theory. Science Almanac of Black Sea Region Countries. 2025;11(4):19-28. https://doi.org/10.23947/2414-1143-2025-11-4-19-28